By: Paul Gehm, Management Analyst, SCAO Friend of the Court Bureau

[ED. NOTE: This article is reprinted with permission of the author and originally appeared in the State Bar of Michigan Family Law Journal, April 2015.]

Michigan has a longstanding reputation as a leader in addressing issues concerning the care and support of children. Ninety-six years ago, the friend of the court (FOC) office was created in part to determine if children regularly received support. Today, the FOC is responsible for recommending the proper amount of support as more families than ever are affected in some way by a child support order.[1] In Michigan as of 2013, the child support program caseload included 952,805 children, and roughly one in four Michigan residents.[2]

“The Michigan Child Support Formula is likely the most comprehensive guideline of any in the nation,” according to William Bartels, a State Court Administrative Office’s Management Analyst who has been assigned to review the formula manual since 1997. “Because use of the formula has become so routine in daily domestic relations practice, many have forgotten or do not realize the substantial changes caused by having a single statewide method by which support obligations are figured.” As family dynamics continue to change, understanding the policy decisions and history of the child support guideline will help inform future changes in how child support is calculated. This article will provide some of that history –highlighting significant events, discussing guideline models, and describing the development and review process of Michigan’s guideline. Finally, the article will provide an overview and comparison of the nation's guideline models.

Michigan’s Child Support History

Historically, child support had been considered as part of an alimony award.[3] Eventually, courts began to address child support separately with most courts addressing the child support amount on a case-by-case basis. However, this led to a large disparity in support amounts.[4] As a result, children were not being treated equally. Grassroots efforts sprang up in response to this inconsistency, and local courts began to develop their own means to ensure that similar cases had similar support orders, many of which were flat percentages of a payer’s income.

Federal Legislation and Regulations

By 1980, circuit courts were using a wide variety of locally established standards for setting child support. In Public Act 294 of 1982, the legislature assigned the responsibility for developing a statewide child support guideline to the newly formed Friend of the Court Bureau (FOCB), a department within the State Court Administrative Office (SCAO). SCAO formed a Child Support Guideline Committee and it began its substantial effort in 1983. In 1984, the federal government required the development of statewide guidelines.[5] To meet the federal mandate, state guidelines were required to meet minimum standards.[6] Several years later, federal legislation added the requirement that the amount calculated by the state guideline would be the presumptive child support amount; however, this legislation and resulting regulations allowed child support orders to deviate from the guideline's presumptive child support amount.

Michigan’s First Guideline

The Child Support Guideline Committee extensively reviewed child support methodologies used in Michigan and nationally, held public hearings, conducted original research, and received input from professional economists and other researchers. Michigan published its first guideline in 1986, taking effect in 1987. In developing its guideline, Michigan looked at seven models for determining a child's support needs before choosing what have now become the three most commonly used state models: income shares, percentage of income, and the Melson model. Ultimately, the income shares model was chosen.

|

National Child Support Guideline Models |

||

|

Income Shares |

Percentage of Payer Income |

Melson |

|

A child whose parents are not in the same household should receive the same proportional share of each parent’s income as a child in an intact household. Therefore, both parents’ income is considered. The economic costs of a child (or the same number of children) in an intact family are prorated based on each parent's share of the total family income. |

A parent’s support is determined by applying a predetermined percentage to the obligor’s income (whether gross or net varies by state). States vary in the predetermined percentage to apply. The obligee's income is not considered. |

Based on the “recognition that parents need to be able to meet their basic needs first and establishes a self-support reserve for both parents” and then the parents' own economic status should not be enhanced until the parents jointly and in proportion to their shares of family income, meet the basic poverty level needs of their children. |

A primary reason why Michigan originally chose the income shares model was that it “not only considers both parents’ incomes but the parents’ relative incomes in the calculation of support. The committee perceived this as being an equitable approach.”[8] Although Michigan chose the income shares model as the basis for its guideline, Michigan never applied a “pure” income shares model. Bartels believes, “Those that developed our original guideline started with a standard income shares engine and modified it to perform well under greatly varying conditions.” He continued, “Nearly every time that I evaluate what other states are presently doing with their guidelines, the more I appreciate the fantastic foresight our committee had when they built several features into their original design.”

From the beginning, Michigan’s guideline took into account additional factors that many states added later, or that some still do not include. Originally, most states’ guidelines did not address how parenting time financially affects a child's support needs; Michigan’s guideline specifically reduced support based on the fact that a parent provides direct support during parenting time.[9] Additionally, rather than setting amounts based solely on economic estimates and parents’ incomes, Michigan’s guideline included a means to allow low income parents to retain a higher percentage of income for self-support, as well as incorporating each family’s specific child care costs and medical expenses.

Underlying Principles for the Guideline

There are several concepts and principles underlying Michigan’s guideline that are worth noting.[10] The primary focus is on the needs of the children. To maintain the child’s needs, children should be financially supported by both parents.[11] Thus, the Michigan guideline determines the support obligation for both parents. The paying parent’s responsibility is what is seen as the child support order, whereas the recipient parent is presumed to contribute his or her share directly to the child’s support. To address this issue, the general cost of care calculation is used.[12] Support is based on estimated expenditures of a similarly situated intact family (similar income levels and number of children).[13] As income rises, so too does the cost of care.[14] In recognition of shared parenting time, the guideline also includes the principle that as parents spend more time with their child, the parent will directly contribute a greater share of the child’s expenses. It is also expected that the child’s standard of living should not be worsened due to the parent’s divorce or separation.[15]

Deviations

While the guideline set the presumed amount of child support, an important aspect for courts is the ability to deviate. However, the court may only deviate from specific provisions that the court deems are unfair or unjust; the rest of the outcomes from the guideline must be followed.[16] The Michigan Child Support Formula Manual provides guidance on some circumstances that are deemed to cause valid reasons for deviations. Some examples include: the child has special needs; a parent is a minor; a parent has a reduction in income due to extraordinary levels of jointly accumulated debt; and a parent receives bonuses that vary or are irregular.[17] Additionally, the parties may agree to deviate.

Guideline Reviews and Revisions

Every four years, the federal government requires a state to review its guideline to ensure appropriate child support award amounts. One of the main focuses of the review is to look at the reasons for deviations and decrease the number of deviations. To do this analysis, SCAO convenes a committee to assist with the evaluation and propose substantive changes. Additionally, when new manuals are released, SCAO incorporates changes required by statute, case law, or regulation and makes economic updates due to changes in the cost of living or federal poverty guidelines. [18]

Since the creation of the guideline, there have been several changes. The following table provides an overview of five important revisions made to the manual since its inception.

|

Issue |

Earlier Provision |

Updated Provision |

|

Parenting Time Costs and Savings |

For cases where parents exercised less than 128 overnights, the friend of the court gave parenting time abatements and had to manually credit cases after 6 or more overnights occurred. For cases where parents exercised 128 or more overnights, a Shared Economic Responsibility Formula was applied that gave a substantial reduction in the amount of support paid or received. Having two provisions led to many disagreements to keep parenting time over or under the 128 day threshold. |

Now, one equation applies to all cases, the Parental Time Offset. This allows for a more gradual reduction of support as parenting time increases to refocus parenting time to its true purpose of access to both parents instead of the economic benefits increased parenting time might provide.[19] |

|

Clarity and Citation |

Language tended to be technical and provisions were hard to locate. The manual was organized in a traditional outline format, which made it difficult to locate and cite provisions. |

Language was simplified and updated. The manual was also restructured and renumbered to allow easier location and citation of specific provisions. |

|

Insurance and Medical Expenses |

Regarding insurance, the parent’s cost of providing insurance was a deduction from income. The manual was silent on picking which parent should provide coverage. Out of pocket medical costs were ordered split based on percentage of family income, and paid after the actual expense was occurred. |

The nonproviding parent’s share of the other parent’s cost of covering the children is incorporated into the monthly support payment. The manual and supplement provide directions on choosing which parent should be ordered to provide coverage. Out of pocket medical expenses are normally paid as part of the monthly support obligation; extraordinary amounts of medical expenses are still reimbursed based on actual expenses occurred. |

|

Low Income Payer |

Michigan’s guideline included a means to allow low income parents to retain a higher percentage of income for self-support reserve. The guideline required a mandatory minimum support obligation (e.g. $25 per month). Once the parent started earning more than the low income threshold, dollar for dollar increases in income were added to the support obligation until the amounts met standard economic levels. Child care costs were allocated based on the parents’ share of family income. |

The manual still allows low income payers a reduced obligation for self-support. The minimum support obligation was eliminated, so support could be based on a parent’s actual ability to pay. Although they pay an accelerated amount for increases in income, the dollar for dollar increase is no longer used. Child care costs are still allocated based on share of family income; however, a deviation is permitted if a parent’s share is greater than 50 percent of the base support. |

|

Parents’ Other Children |

If there was a support order for a parent’s other children that order amount was subtracted from the parent’s income in the case under consideration. This caused large differences in amounts ordered for the same number of children in different cases. For children in the parent’s household, the parent received a percentage reduction to their income.

|

All children-in-common with the same other parent are included in the calculation for support. The support paid between those parents is the same whether in one case or multiple cases. For children with someone other than the other parent in the case, the parent receives a percentage reduction to their income regardless of whether the children are in their household or in a separate support order. |

Comparison with Other States

Administrative Structure

While requiring states to develop a guideline, the federal government gave the states flexibility in doing so. There is great diversity across the nation in how states implement and manage their guideline. According to data from 2011, eighteen states (including Michigan) develop their guideline through the judiciary; five states use a legislative process; another eighteen states’ laws delegate authority to a state agency or special commission with legislative oversight; and nine states authorize a state agency or special commission to maintain the guideline with no legislative oversight. [20]

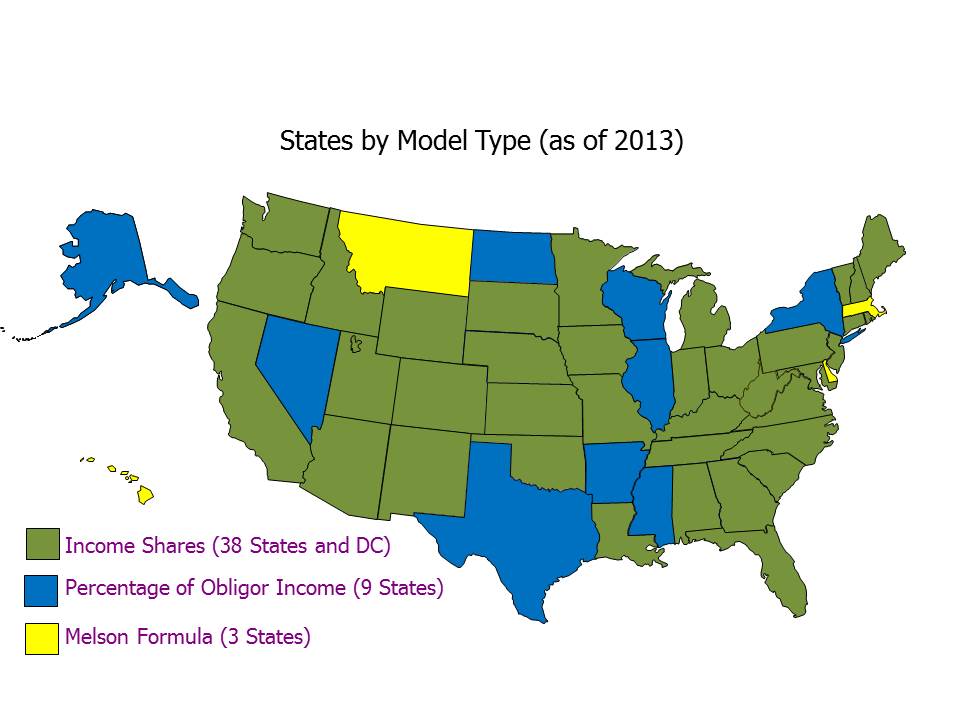

State Models

There continues to be variety in the implementation of the various models used nationwide.[21] Although the income shares model is the most commonly used, not all states strictly apply the model. The percentage of income model is the second most widely used; however, there is a trend to move away from this model (and to the income shares model). Finally, only three states use the Melson model. Since 1990, nine states have switched models – all but one to the income shares model.[22] One reason for this shift is the perceived fairness of the income shares model. It is believed that this perception results in increased child support collected.[23]

Michigan’s Comparison

National experts look to Michigan as a leader in child support issues, especially the guideline. “Michigan has one of the most comprehensive guidelines in the nation.”[25] One of the reasons for this is the continuous updates and modifications that are routinely made to respond to economics. “Michigan has been more than diligent at fulfilling [the guideline review] Federal requirement.”[26] In contrast, there are eight states that have not updated their guideline in any capacity.[27] According to a recent study, Michigan's efforts have paid off by placing its support obligations within a range that results neither in excessive support obligations nor in support that is inadequate.[28]

Conclusion

For the most up-to-date information, visit the SCAO Child Support website at: http://courts.mi.gov/administration/scao/officesprograms/foc/pages/child-support-formula.aspx. There, you can find information on the current guideline and updates to the supplement. The old manuals are also archived on this site. Finally, there are webcast trainings available on basic and intermediate child support concepts.

Michigan’s guideline continues to lead by addressing difficult issues. The guideline has adapted to address former criticism and now is seen as innovative and more successful. Unlike some states that have not updated their guideline at all, Michigan’s guideline has seen significant changes and routine modifications. The next round of review will begin soon for the revisions to be released in 2017. As the next and additional reviews approach, Michigan will continue to update the guideline to meet current economic trends as well as address substantial issues as our state continues to set the example for guidelines nationwide.

[1] Anne C. Case, I-Fen Lin, and Sara S. Mclanahan, Explaining Trends in Child Support: Economic Demographic, and Policy Effects, Demography, Vol. 40, No. 1, Feb. 2013, p.171.

[2] OCSE 2013 Annual Report to Congress, Table P-93, available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/css/resource/fy2013-preliminary-report-table-p-93. To estimate the 25 percent, start with the 952,805 children, assume two parents for each child (understanding this will double count some, while excluding others such as third party custodians), then divide by the total population from the US census data. This is meant to serve as a rough estimate to show the large impact the program has in this state.

[3] See Welles v. Brown, 226 Mich. Reports 657 (1924).

[4] A Denver study found support orders for a child ranged from 6 to 33 percent of a noncustodial parent’s income. Child Support Manual and Schedules, Friend of the Court Bureau, 1986, pg 2.

[5] Child Support Enforcement Amendments of 1984 (Pub. L. 98-378).

[6] There are now three minimum requirements: consider all earnings and income from noncustodial parent; use descriptive and numeric criteria; and address how a child’s health care needs will be met. 45 C.F.R. 302.56 (2014).

[7] For a more detailed discussion of the three main models, see Dr. Jane C. Venohr, Child Support Guidelines and Guidelines Reviews: State Differences and Common Issues, Family Law Quarterly Vol. 47, No. 3 (Fall 2013) p. 329-332; see also Laura Wish Morgan, Child Support Guidelines: Interpretation and Application §1.03 (1996), available at http://www.supportguidelines.com/book/chap1b.html#1.03.

[8] Jane C. Venohr and Tracy E. Griffith, Report on the Michigan Child Support Formula, Public Studies Inc., April 12, 2002, p. 107.

[9] Kentucky and Washington still struggle to address parenting time issues in their guidelines.

[10] For a full discussion of the policies and assumptions behind the income shares model, see Original Guideline, pp. 12-14.

[11] David A. Price, Michigan Child Support Formula: Findings from a Survey of Formula Users, (PSI, June 17, 2002. p. 12). As a general rule, support “should be apportioned between the parents based on each parent’s percentage share of their combined net incomes” (2013 MCSF 3.01(B)).

[12] The guideline uses the 1972-73 Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES) Child Support Manual and Schedules, Friend of the Court Bureau, 1986, pg 15. The guideline also relied on the Epenshade study. Child Support Manual and Schedules, Friend of the Court Bureau, 1986, pg 15.

[13] Child Support Manual and Schedules, Friend of the Court Bureau, 1986, pg 12.

[14] Child Support Manual and Schedules, Friend of the Court Bureau, 1986, pg 12.

[15] Children should not suffer due to their parents’ divorce or separation. David A. Price, Michigan Child Support Formula: Findings from a Survey of Formula Users, PSI, June 17, 2002, p. 12.

[16] 2013 MCSF 1.04(B). See also, Burba v Burba, 461 Mich 637 (2000) (ruling that the courts were limited to deviations based on facts which were specific to the case and which were not taken into account by the formula).

[17] 2013 MCSF 1.04(E).

[18] To independently verify that its ongoing updates continued to produce acceptable results, the State Court Administrative Office contracted with Policy Studies Inc., for an independent analysis of Michigan’s guideline. Report on the Michigan Child Support Formula (issue April 12, 2002) by Dr. Jane C. Venohr and Tracy E. Griffith., focused on several key topics, including: a comparison to recent economic studies, a comparison to other states’ models, and perceived fairness.

[19] Bartels explains, “When I evaluated the original proposal from Kent Weichmann and Craig Ross, it seemed to solve the biggest issue people had with our guideline. Since it was adopted, that single change annually eliminated tens of thousands of account adjustments that friend of the court offices had to make and cut the number of complaints that SCAO had to handle about the formula by at least 70 percent.”

[20] For further discussion, see http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/child-support-process-administrative-vs-judicial.aspx.

[21] For a detailed discussion of general national trends and approaches to key issues such as: shared parenting time, low income, deviations, additional dependents, and nontraditional families, see Child Support Guidelines, pp. 340–46.

[22] Venohr, p. 332.

[23] Noyes, p. 17.

[24] For a look at each state’s model, the income base (net or gross) and the last update to the core formula, see Venohr Table 1, pp. 330-31.

[25] Price, p. 4.

[26] Price, p. 1.

[27] Venohr, p. 336.

[28] This study includes a summary chart with the three example cases. Venohr, pp. 346-350.